‘Normal' Does

not mean Optimal.

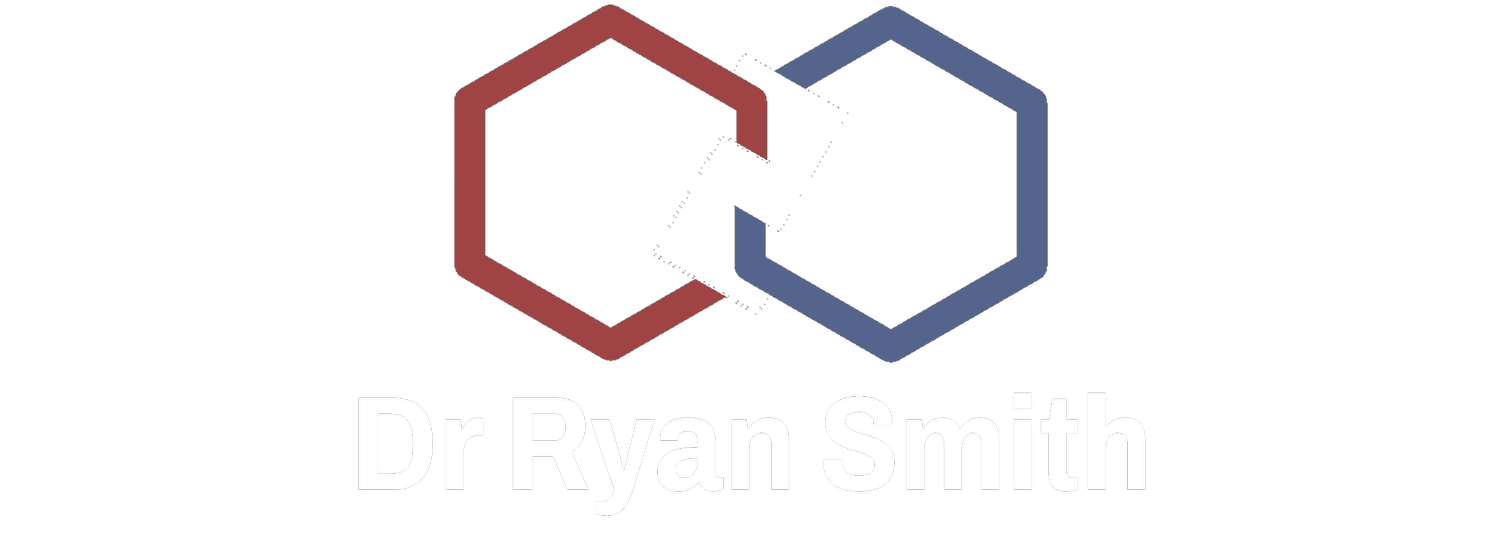

Most labs formulate their reference ranges using normal distribution, whereby the middle 95% of a healthy population’s results are considered normal, and the 2.5% on either end are classified as abnormal. This method provides benefit when people are acutely unwell, allowing for easy interpretation by creating clear cut-offs for disease.

However, this over-reliance on statistics means a ‘normal’ result may correspond to the absence of overt disease, but not ideal physiology. These ranges lead to a reactive approach to healthcare; trends towards dysfunction are often overlooked until they cross the pathological threshold.

In the world of human performance, this method does not work. A new gold standard is required because if you compare yourself to the average, you will become the average.

Creating Reference Ranges that Matter

By comparing results from high-performing athletes and using research on the cutting edge of peak performance and longevity medicine, reference ranges can be formed that actually correlate with high-level results.

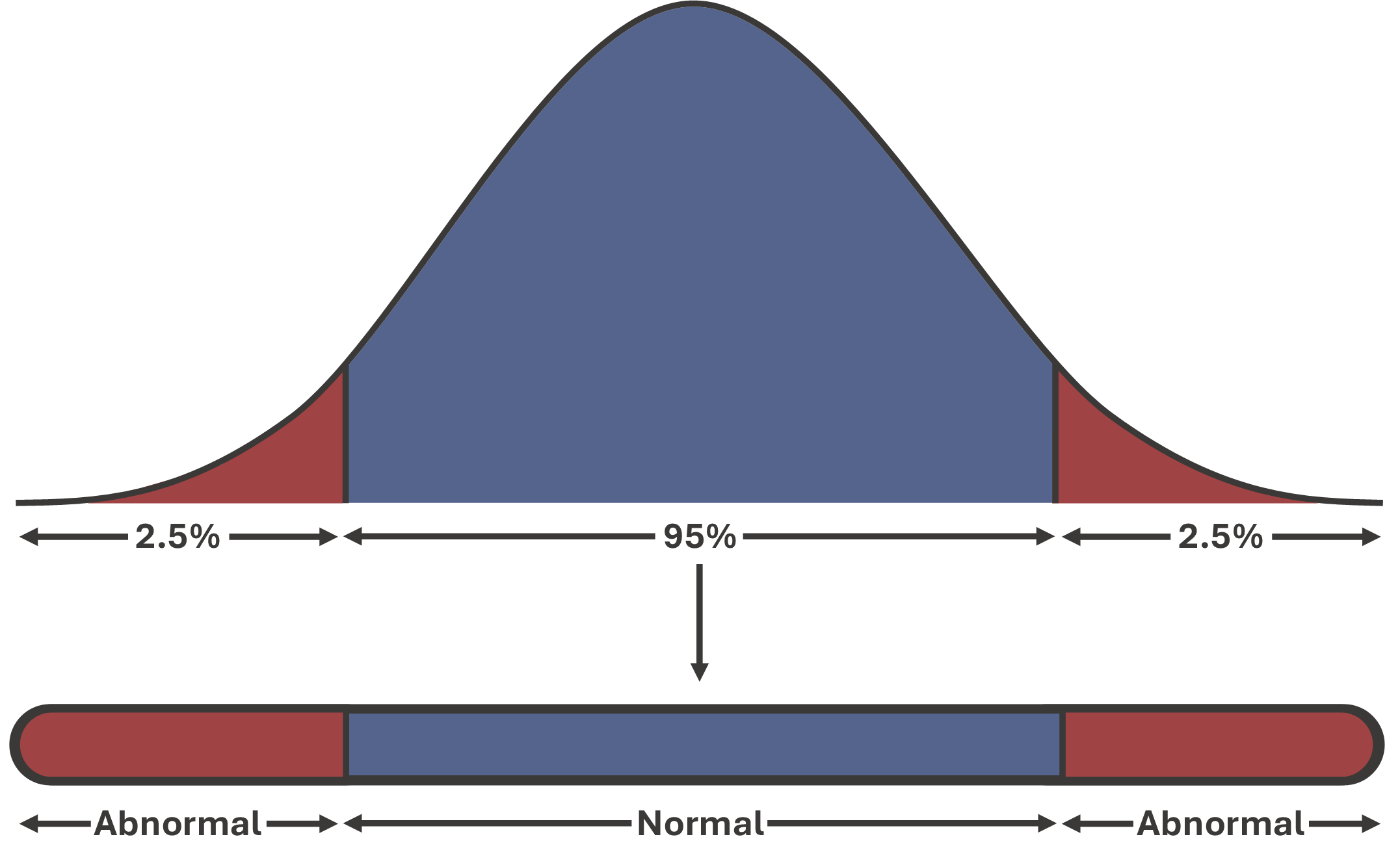

Standard values are either ‘cut’, ‘compressed’ or ‘conveyed’ (or often a combination of all three) to reflect physiology, not statistics.

CUT Ranges

Some biomarkers should stay low. Auto-antibodies, cardiac enzymes and many inflammatory markers fall into this group—any rise, even within the 'normal' range, can signal early dysfunction.

Others, like vitamins and minerals, are best kept as high as safely possible, as the lower end of 'normal' can still reflect a subtle deficiency.

Compressed Ranges

Most biomarkers don’t just need a high or low cut—they function best within a sweet spot.

Take electrolytes like sodium and potassium. Too high or too low—on either side—can disrupt the body’s physiological balance. Even the ratio between them matters.

CONVEYED Ranges

Sometimes what is best for your health, is not always best for your sport.

Optimal performance ranges can be shifted into the abnormal range, where performance benefits can be obtained at a potentially increased risk to health.

The benefits vs. risks need to be weighed up on an individual basis to decide what limits are prepared to be pushed.

See THE DIFFERENCE

‘OPTIMAL’ REFERENCE RANGES MAKE